Copper Etching Experiments

Exploring printmaking through adaptation and new processes.

As part of the ongoing development of the ‘imprints’ project, I wanted to explore new (to me) printmaking techniques — revisiting my background in printing from my textiles degree, while also expanding my technical skills as an artist. A key part of this is adapting traditional processes to work around the facilities available and making them as accessible as possible, since I’m tetraplegic and unable to use my hands.

Etching immediately stood out to me. There’s something compelling about a technique that’s medieval, but is still used in making contemporary and abstract work today. Often used for cartography and fine line drawing, etching captures every mark made. I found it interesting to experiment with a process that was so unforgiving because when painting I am used to working into my mistakes until I am happy with them. In etching all mistakes remain in the final piece.

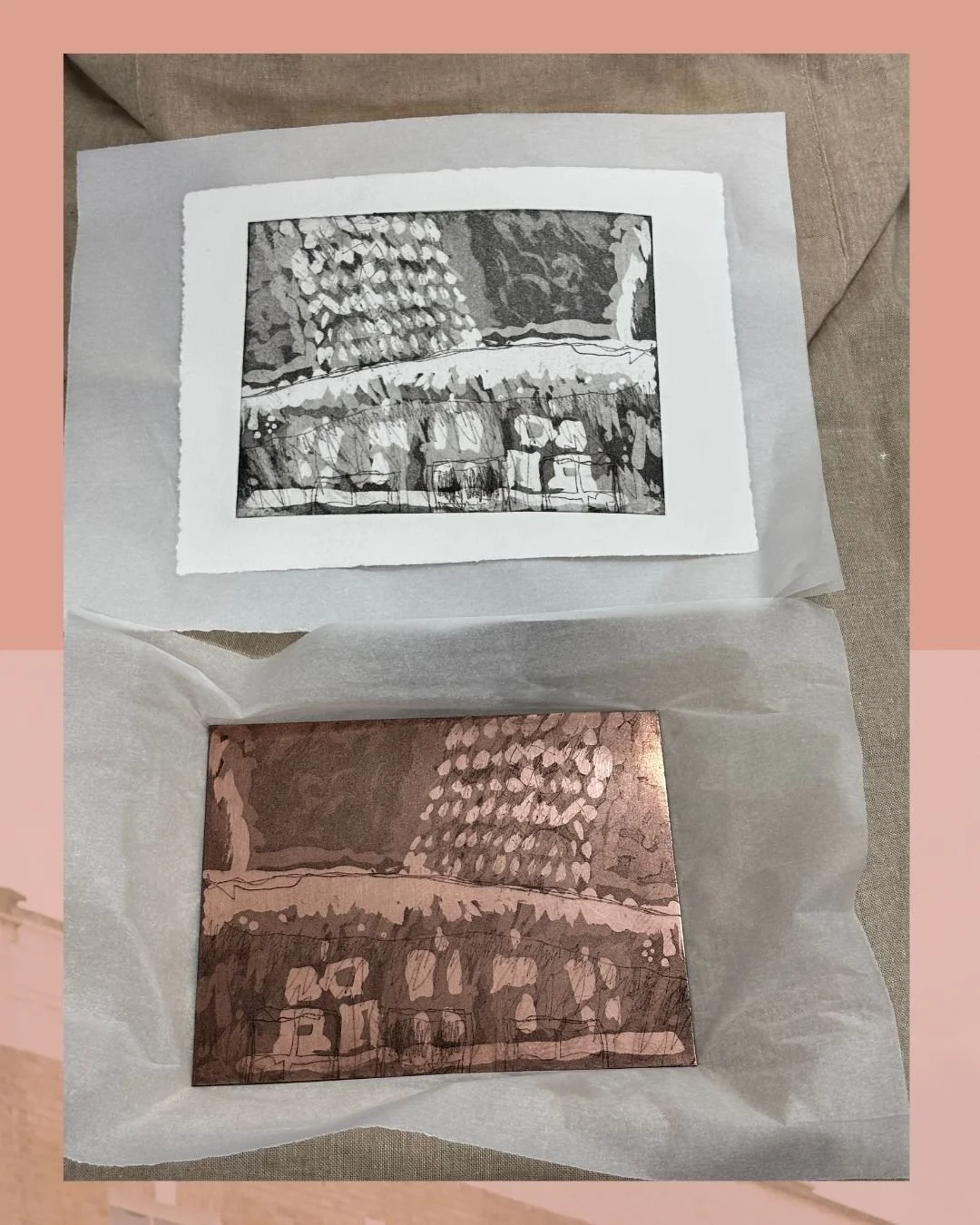

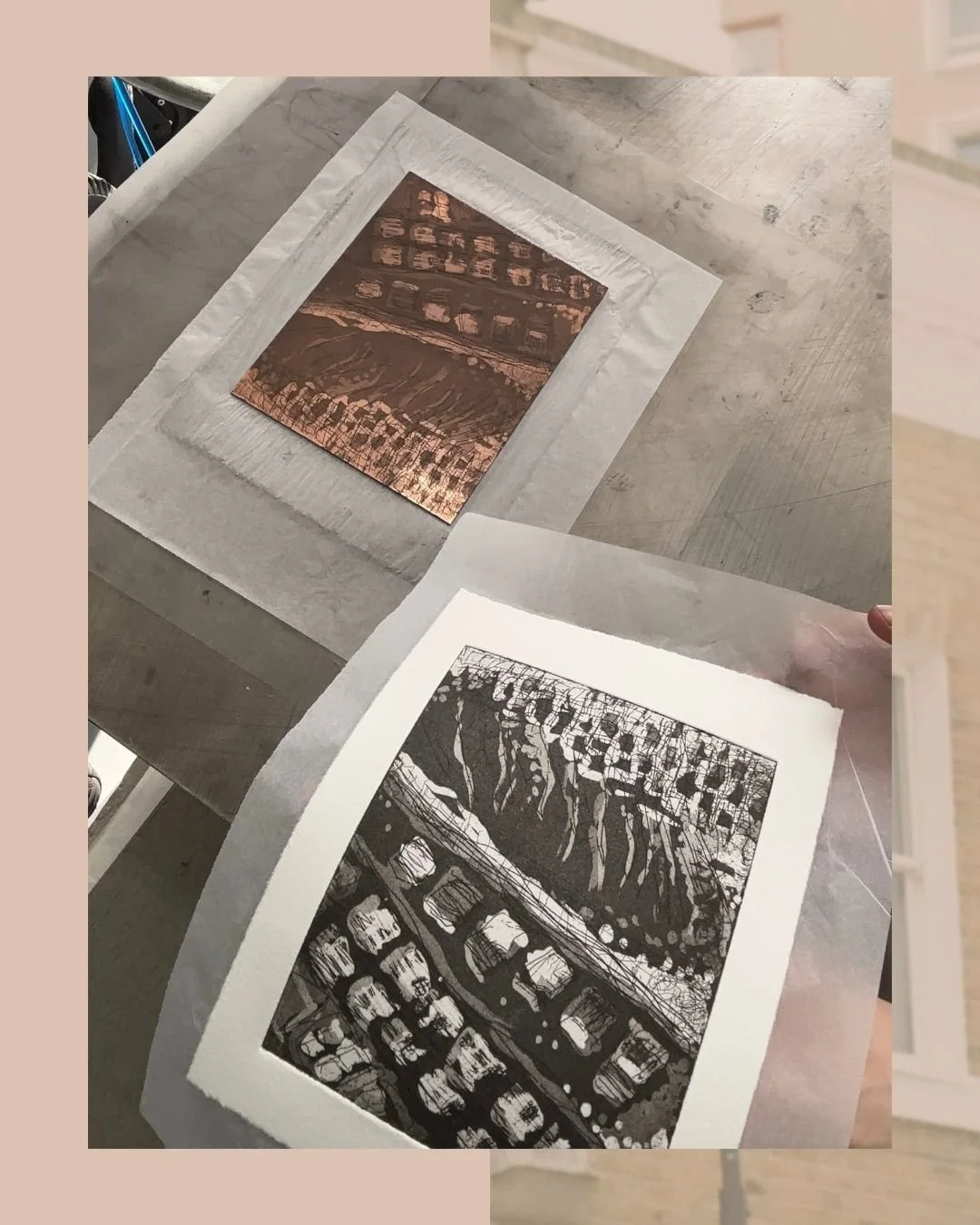

The method involves coating a metal plate with an acid-resistant ground, which is then scratched or removed in places to create an image. When the plate is submerged in an etching acid, the exposed lines are ‘bitten’ into the surface. These etched grooves hold ink, and when damp paper is placed on top and the whole thing is run through a press, the image transfers — revealing the etched marks in printed form.

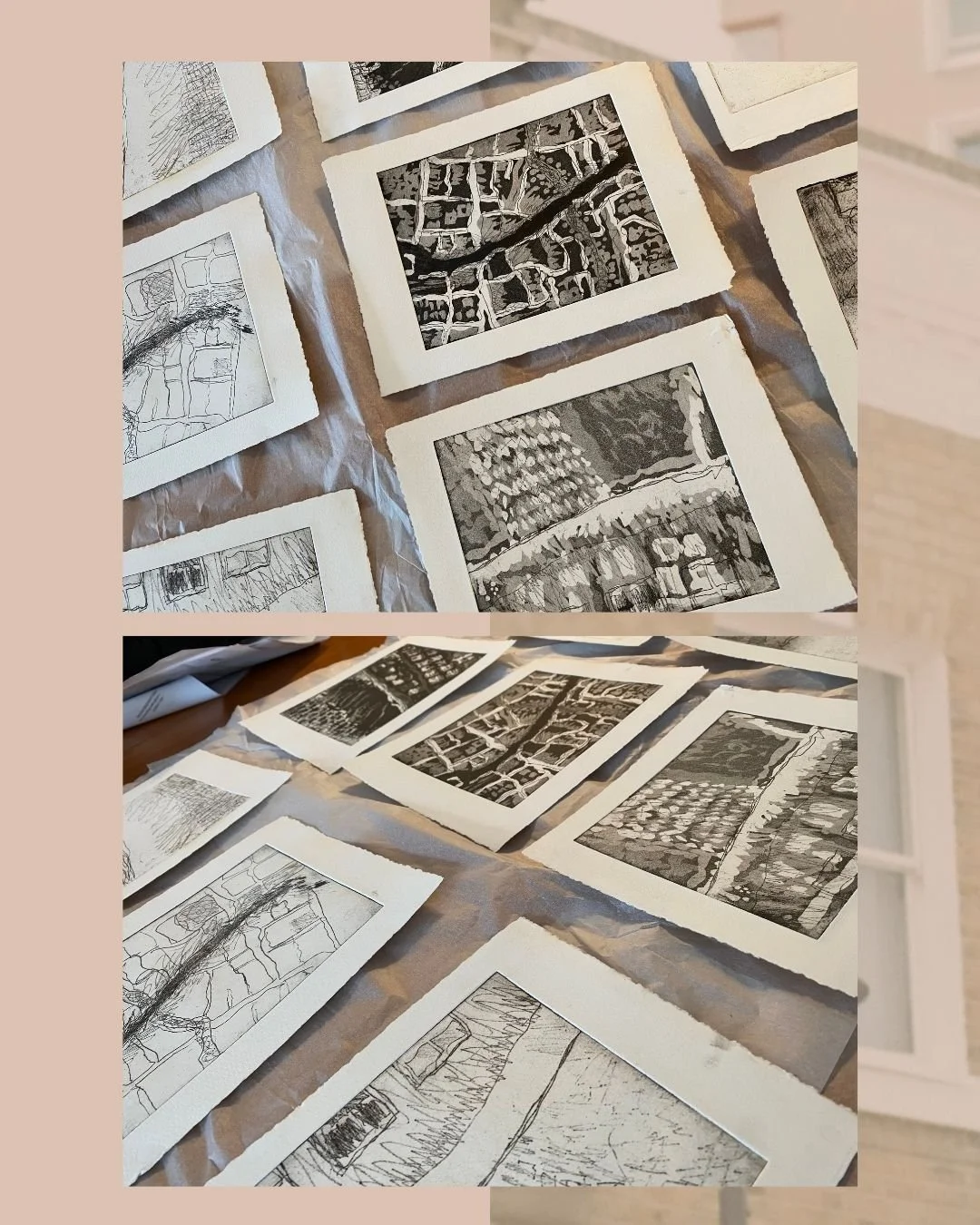

Over the course, I had the opportunity to experiment with the three main types of acid-resist grounds: hard ground, soft ground, and aquatint. Each brings a unique quality to the final image — from sharp, detailed lines to soft tonal effects — and they can be used either individually or layered together on a single plate for more complex results. It was exciting to experiment with a process that had so many different stages because it forced me to be slower and more methodical in my mark making.

This process not only offered new visual possibilities but also became a space for me to adapt and reimagine how these traditional techniques can be made more accessible.

While in the studio, my tutor Ann worked closely with me to adapt the space. Etching acid bowls were positioned within reach, and I used a range of hand splints, protective gloves, and tape so I could draw into the ground, roll it out, and etch the plates myself. There was also a large press which I was able to use with some practice. Being able to physically carry out these stages felt deeply satisfying. The process demanded constant problem-solving — negotiating the weight of the roller, the reach required to access the acid, and the timing of each stage — but that friction became part of the work rather than an obstacle to it.

Being in the studio felt both challenging and energising. The whole process requires much patience and repetition, with playful and absorbing moments when I was etching into the plate or applying the Aquatint. Using the press and rolling the plate were physically tiring, but they were punctuated by small moments of satisfaction and relief — a mark holding correctly, a plate biting cleanly, a tool adaptation that we worked on together working better than expected. Those successes carried a particular weight because they were hard-won. It was exciting to push the boundaries of what felt possible, both artistically and physically — finding new ways to make, mark, and map through print.

The support I received was essential, but it was also carefully balanced. Adaptation didn’t mean relinquishing authorship. Alongside collaboration, it allowed me to engage directly with the material and the process.

The qualities of etching itself felt uniquely suited to this project. The way ink settles into bitten lines, holding evidence of pressure, duration, and contact, mirrors the themes I’m exploring in Imprints. Etching records touch in forensic detail every hesitation, drag, mistake, smudge and fingerprint is preserved in the plate. Each decision is archived within the print. The ink becomes embedded in the surface rather than sitting on top, suggesting permanence, memory, and trace.

Working with ferric chloride and copper also introduced a slower, more durational rhythm to my practice. The waiting, the repeated checking, the irreversible nature of each bite encouraged a more attentive relationship with the process. Etching resists immediacy; it asks for commitment and acceptance of marks once they are made. That quality — the inability to undo — resonates strongly with the conceptual framework of the project, bringing both material and metaphor into alignment.